E.T. Noar - Penshurst Tailor 1903 to 1919.

Edmund Theophilus Noar was born in 1879 at Gaffney’s Creek Victoria. His parents were Alfred and Isabel Graham (Adcock) Noar. Edmund was one of 10 children. He had seven sisters and two brothers. Edmund married Oenone Idalia Manderville in 1901 she was born at Richmond in 1879; her parents were Frederick Augustus and Emily (Tucker) Manderville. Edmund and Oenone had five children.

- Viola Myrtle Noar born in 1903 at Port Fairy.

- Ivy Manderville Noar born in 1905 at Penshurst.

- Frederick Albert Noar born at Penshurst in 1909.

- Charles Edmund Noar born at Penshurst in 1914.

- Alfred Manderville Noar born at Penshurst in 1918.

It would appear that Edmund went to live in Port Fairy where his brother Alfred Henry Noar was living. Alfred was a well known identity in Port Fairy where he was a Tailor and involved in local and State politics. Alfred was married to Augustine Sarah (Emery) Noar and had four children. He was the Mayor of Port Fairy on numerous occasions and he ran for State parliament in 1917 for the Liberal party but was unsuccessful.

“Port Fairy Gazette (Vic)), Thursday 22 November 1917” “State Election. PORT FAIRY STATE SEAT. DECLARATION OF POLL. There was a delay in declaring the result of the poll at Port Fairy, owing to the declaration from the Framlingham West deputy returning officer not being in order. This morning, Major Kell, returning officer, formally declared the result of the poll as follows: Votes. HENRY STEPHEN BAILEY 3317 ALFRED HENRY NOAR 1691 Informal 75. Majority for Bailey, I826”

Edmund Theophilus Noar certainly had an illustrious brother to look up to and further his connections with local dignitaries. Edmund moved to Penshurst in 1903 and started up his own business as a Tailor. He appears in the rate books as renting a shop and dwelling from Phillip Duffy Collins in 1903.

In 1908 he moved from that shop to a new shop that he rented from James George Chesswas on part allotment 5 section 17. Edmund left Penshurst and went to live in Nagambie with his family. He died in 1963 and his wife Oemone Idalia died in 1971. Both are buried at Nagambie Cemetery with no headstone.

Their children:

Viola Myrtle married Joseph Boston. She died in July 1984 at Nagambie.

Ivy Mandeville married John Henry Muller and she died in August 1982 at Nagambie.

Frederick Albert died in December 1987 in Tasmania.

Charles Edmund married Beryl Gladys Smith on the 7th December 1940 at Bonegilla.

Charles Edmund and Alfred Mandeville both died on active service as Prisoners of War of the Japanese at Ambon.

Charles Edmund and Alfred Mandeville Noar enlisted in the Army together on the 13 June 1940. Both of the boys were born in Penshurst, Charles on the 12th July 1914 and Alfred on the 4th June 1918.

VX 31179 Private Charles Edmund Noar enlisted at Malvern Victoria. His next of kin was Edmund his father. He listed his occupation as Clerk.

VX 31176 Corporal Alfred Mandeville Noar also enlisted at Malvern and his next of kin was Edmund his father.

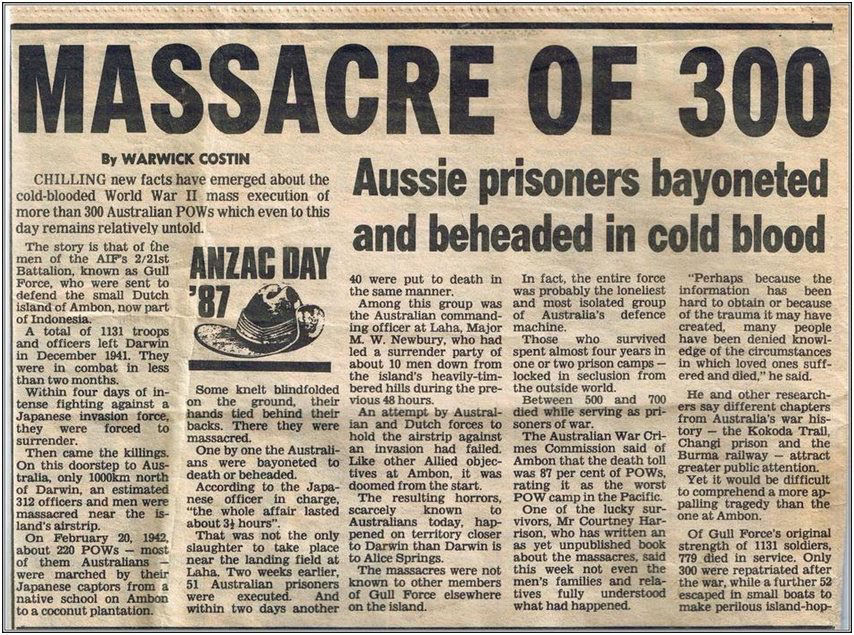

The following history of the ill fated 2/21st Battalion applies to both brothers.

The 2/21st Infantry Battalion, part of the 23rd Brigade of the 8th Division, began assembling at Trawool in central Victoria on 11 July 1940. Approximately half the recruits were from Melbourne and the rest from rural Victoria. Training was conducted at Trawool until 23 September when the battalion began to move to Bonegilla, near Wodonga on the New South Wales–Victoria border. It made the 235 km journey on foot, arriving on 4 October. Training soon resumed and occupied the battalion until it commenced another move on 23 March 1941 for Darwin in the Northern Territory. It had been earmarked to reinforce Dutch troops on the island of Ambon in the event of a Japanese attack. Although military sense dictated the battalion should be deployed as early as possible, to prepare defences and train in the conditions in which it would fight, it was thought a premature deployment may provoke Japanese action. Thus, the battalion would be held in Darwin until Japan’s intentions were clear.

The 2/21st began arriving at Darwin on 9 April. Its nine-month stay was not a happy one and the primitive amenities, isolation, and mundane garrison duties lowered morale. Operational training continued but was impeded by a shortage of equipment, supplies, and ammunition, as well as the demands of other duties. On 8 December news of long-expected Japanese attacks arrived and five days later the battalion was on its way to Ambon to join elements of the 18th Anti-tank Battery, 2/11th Field Company, 2/12th Field Ambulance, and other supporting troops to form “Gull Force”. The commanding officer of the 2/21st, Lieutenant Colonel Leonard Roach, despaired at the situation facing the battalion: cooperation with the Dutch forces was difficult; transport, air and artillery support, and reserves of rations and ammunition were limited; and the combined Australian and Dutch force, numbering 3,700 troops, was likely to be overwhelmed by the larger Japanese force.

The Australian battalion group of about 1100 men known as 'Gull Force' had arrived in Ambon on 17 December 1941 after a three-day trip from Darwin. The group comprised the 2/21st Battalion, which was part of the 23rd Brigade, 8th Australian Division, together with anti-tank, engineer, medical and other detachments. Their task was to join Netherlands East Indies troops - about 2500 men - to help defend the Bay of Ambon and two airfields at Laha and Liang. The Dutch commander, Lieutenant-Colonel J R L Kapitz, was senior to the Australian commander, Lieutenant-Colonel L N Roach, and took control of both forces, dispersing them into two groups. One group was sent to defend the airfield at Laha on the west side of Ambon Bay and the others were deployed to the east of the bay, south of the town of Ambon. Both the Australian and the Dutch forces were inadequately prepared and under-equipped. Lieutenant-Colonel Roach, aware of the futility of their task, made repeated requests for reinforcements of both men and equipment from Australia, even suggesting that Gull Force should be evacuated from the island if it could not be reinforced. Instead, he was recalled to Australia and Lieutenant-Colonel John Scott, a 53-year-old Army Headquarters staff officer from Melbourne, replaced Roach as commanding officer of Gull Force in the middle of January.

On the eve of invasion, Scott relocated many of the defensive positions, leaving the battalion even less prepared for the Japanese invasion. Three battalions of Japanese infantry and a battalion of marines landed on the night of 30 January 1942. Within 24 hours the Dutch forces surrendered and Roach’s dire prediction ultimately came to pass. Despite instances of brave, determined resistance, the 2/21st could not hold back the Japanese. On 2 February B and C Companies were massacred around Laha Airfield. The remainder of the battalion surrendered on 3 February and were imprisoned at their former barracks on Tan Tui.

On 25 October 1942, about 500 of the Australian and Dutch prisoners were sent to Hainan, an island in the South China Sea off the coast of mainland China. Led by Lieutenant-Colonel Scott, they left Ambon in the Taiko Maru and arrived in the Bay of Sama on Hainan Island on 4 November. The next day they sailed up the coast to a camp at Bakli Bay.

The Japanese government had recognised Hainan Island's potential and planned to use the POWs to build roads and viaducts in order to develop agriculture and industry on the island. The prisoners were forced to do hard manual labour under difficult and brutal conditions with a completely inadequate diet. By 1945 the survivors were all starving. Worse still, Scott was an unpopular senior officer who was unable to command the respect of his troops. His unpopularity increased when he organised Japanese rather than Australian discipline for men who violated Australian army regulations. Early in 1944, 40 of the Australians were sent to work at the Japanese garrison at Hoban, north of Bakli Bay on Hainan. While out on a work party one morning, they were fired on by Chinese guerrillas, some of several thousand nationalist and communist guerrillas were still operating against the Japanese on the island. Nine Australian POWs were killed, three were wounded and ten others were captured by the guerrillas but were never recovered.

Conditions for the prisoners on Ambon were harsh and they suffered the highest death rate of any Australian prisoners of war. A contributing factor was the transfer of all but a small number of medical personnel to Hainan Island on 25 October 1942.

VX31179 Corporal Charles Edmund Noar died of Beri Beri on the 17th July 1945 aged 31 years at Tan Tui prison camp on Ambon. Charles died just weeks away from being liberated. He is buried at Grave Reference: 18. D. 4.Cemetery: Ambon War Cemetery.

VX31176 Lance Corporal Alfred Mandeville Noar died on the 19th December 1943 aged 25 years at Tan Tui prison camp on Ambon. He is buried at Grave Reference: 23. C. 11.Cemetery: Ambon War Cemetery.

At the end of August 1945, Americans liberated the POWs from Hainan. On Ambon the surviving Australian POWs waited another four weeks to be rescued by the Royal Australian Navy corvettes, HMAS Cootamundra, Glenelg, Latrobe and Junee. The very high (over 75%) death rate on Ambon had been exacerbated when an American bomber dropped six bombs on the Japanese bomb dump right next to the Tan Tui POW camp. The dump ignited and exploded, killing six Australian officers, including the doctor, four other ranks and 27 Dutch women and children. A number of Dutch and Australian casualties died later.

After the Japanese surrender it was discovered that about 300 servicemen who had surrendered at Laha airfield had been killed in four separate massacres between 6 and 20 February 1942. Not one had survived. The prisoners on Ambon and Hainan were subjected to some of the most brutal treatment experienced by POWs anywhere during World War II. Over three-quarters of the Australian prisoners there died in captivity.

“News (Adelaide), Friday 5 October 1945”

Support for Ambon inquiry

CANBERRA.-The demand by Mr. Anthony, M.H.R., for .an inquiry into the Ambon force and other Pacific outposts, was supported today by the Leader of the Senate Opposition (Senator McLeay). Senator McLeay said the inquiry should be independent, and should deal generally with the facts.

These would show why no action was taken to withdraw the garrisons from such outposts when it became evident that they would be annihilated if left at their posts. The inquiry should deal particularly with the serious allegation that the commander of the Ambon force expressly warned the Government well in advance, of the tragedy which awaited his men, and was removed from his command for his pains.

There was the strongest reason to believe that the first commander of the Ambon force did in fact make an emergency trip to Australia to give the Government the facts and that he was relieved of the command as a result, but this charge had been completely ignored by Mr Forde. The inquiry sought by Mr. Anthony should be made by an authority of a completely independent character.”

Note: this newspaper clipping was sourced from the

National Archives Australia. The newspapers name is unknown.

We would like to thank the following sources for information.

Trove Newspapers

Australian War Memorial

National Archives.

2/21st Battalion website.

by Ron Heffernan, Mount Rouse & District Historical Society Inc. 2015.